THE BEND

Diesel plumes eddied in off the county road and mantled the frozen tug of Apple Creek. Beyond the dip the unending prairie, which had so brightly symphonied in the Fall, yawned now beneath my feet like blighted promise. It was cold. A bitter, marrow-tickling draught picked it’s way between the snowdrifts in my driveway and stole under my kitchen door. I checked the Thermometer. 35 below.

Christmas would take a life or two again this year. In this clime, most especially here in this bracing nook of the upper Midwest, it was expected. Not for the first time I couldn’t help but muse on how magically resilient our triptych of blood, bones and tissue could acclimate to even the most ferocious of weather. I tottered to my feet and crow-hopped to the windowsill. Parting the curtains, I smudged an uneven circle in the condensation and peered out.

I loved a winter sky. But this evening’s display was a diseased firmament. It strung wide and low across the frayed perimeters of Swaying Mesa Reservation like a vaulted cataract over the farmhouse. In short, it did little to alleviate my customary unease this December. But straining my eyes into another calcified North Dakota dusk I found what I’d been looking for.

Lionel Biddle. Standing alone, as always, by the verge of Apple Creek Road. Shoulders bowed. Shifting his weight from one moccasin to the other as he squinted resolutely at the vaporous turn in the ribbon of blacktop up ahead.

Even from here I could see he was clearly mesmerized by whatever he glimpsed there. His inert posture was all but nailed to the hardscrabble soil at his feet. Soon I’d have to head out there once again, scrape the snow from the four-wheeler in the lean-to, kick-start it best I could then rattle on out there to usher him inside. Away from the bad memories and palsied murk that kept him up nights.

My name is Fiona, Fiona Bridget Kinsella. I’m sixty-nine plus, Irishwoman come plainswoman, Kilkenny born and bred. Until I eloped that is, on the broad, burnished arms of a long passed though nary forgotten badlands sweetheart. You know me. At one time or another you’ve encountered me in one guise or another. Sure there’s women like me all over the upper Midwest. Take a closer look. You’ll see a crooked, pitiable silhouette strung about the waist in a Folgers-scuffed apron as I reminisce tirelessly about the Old Country. It’s no secret every morning I look forward to and expect to die. A mindful neighbor would find me in bed, lying prone over a surprisingly crisp coversheet, wantonly expired somewhere inside the tidal indifference of sleep. But, I duly implore you, don’t sum me up with pensive hearts. For I have found a new love to pass my days and nights, a delicate, amiable soul forty years my junior. Sure I’m old enough to be his mother and sometimes play the accustomed role when I deliver the odd chocolate pretzel or leave a half-sipped coffee cup expediently on his stove.

Lionel’s a close neighbor of mine, you see. Real close. He lives and resides about a dozen or so paces to my left in a trim, lilac basement house across the way. Twelve years ago his cherished Hanna, a sweet-natured wife and loving, indefatigable woman perished in the throes of childbirth. She left her husband destitute and their first and only son to rear his infant head into a glaring, motherless world.

Now as it happens I don’t take a mind to children. I simply never have. Too selfish I suppose, self-absorbed. But Francis turned out just grand. An infectiously spirited lad he won my heart right from the get-go. It’s true to say I nurtured a great fondness for him over time.

But a year ago to the day, on Christmas eve, fate spat venom in Lionel Biddle’s face a second time and took Francis from him too. Cruel and unsightly was his exit from the world and that’s all there was to it. That euphonious laughter that jingled on my deck for seven years hung like a stillborn pall on the air between the farmhouses now. Consequently Lionel himself lost the plot, tipped over and gave up the ghost.

Like any self-respecting father he plays it over and over, like some macabre cinematograph pinned to the inside lining of his eyelids. He watches the bus slide and jack-knife. He braces every fiber of his being for the looming trajectory of the Minnesota-sander truck as it bears down the rutted lip of the creek. He does his utmost to shut out the battering envelop of metal as it slams the canary yellow cab of the school bus. The gas now, leveeing into the air as young, unsullied blood telescopes in guttering washes to the snow. Finally there’s the blast. A cannonade of glass, grill, tire and something unsightly. It’s like yarn, Lionel thinks. The shorn bodies of schoolchildren, cut, spun and knitted into the frosted air.

The following morning’s Bismarck Tribune stated that insufficiently lit emergency road works erected just that day to treat a singularly treacherous ice glaze in the road was the sole cause of the accident. Of the seventeen pupils riding the 30 passenger cab eleven died outright, Francis Biddle among them. That very morning had seen him rise on the cusp of a clear day to gather his satchel and kiss Lionel goodbye, scarcely aware it was to be the last time he’d purse those lips so lovingly to his father’s cheek. He’d told Lionel he’d arrive home early, on the 12.10 for sure. He even estimated the bus would be idling for drop off at Apple Creek by 12.30. Officially, school finished days ago, he said. Today was just an informal exchange of Christmas gifts amongst the students and teachers. So while attendance was not mandatory Francis thought it’d be fun to show his face.

And so Lionel, only too happy to catch a smile on his son’s routinely sullen face obliged. He told the boy fine, but he warned the afternoons were dark. He’d pick him up at the Apple Creek stop itself, accompany him on the ill-lit walk across the plains to the house.

Routinely the Apple Creek school bus departs its terminus at Apple Creek Elementary School to wind its itinerary over Maple Bridge gulley, up Coriander Lane to crest the north-easterly bend of Apple Creek itself. It then navigates the old rifle range road by the Tumbleweed Bar to coil eventually alongside the twenty acres that bracket my property and Lionel’s. Lionel estimated he’d collect Francis at 12.25 that afternoon. In fact, he jibbed, he’d even forgo his yearly dosage of It’s A Wonderful Life which was due to air for the umpteenth time on Fox that afternoon. He’d record the movie, he promised, so that they could watch it together later on. But Francis’s attention had been elsewhere, preoccupied as he was giftwrapping a small item, something he’d picked up across the river at Mandan State Fair, for Becky Schumann. Becky was the only daughter of German immigrant dairy farmers, a classmate of Francis’s and, if he had anything to do with it, his first and soon to be proper girlfriend.

Today the Schumann girl reposes in a St Alexis Medical Hospital ward in downtown Bismarck. You could say she was one of the lucky ones. By the time emergency beacons blooded every snowflake that fell upon her crumpled, half slung body, Becky had already lapsed into a deep coma. Lionel, to the best of my knowledge, has never visited her.

So, despite the occasional onslaught of acute dementia (so they tell me) I nonetheless recall the comings and goings from the Biddle residence that day with the clarity of cut crystal (so I tell them).

There was young Francis leaving for school round eight, the season-split wood of the front door protesting against the frame. There was Lionel himself, shoveling slush to either side of the driveway before keying his Ford and leaving for town. I know for a fact he returned almost exactly an hour later. I waved to him. He waved back, smiling. He would leave again only at noon when the first flurries appeared out of the eastern sky, then return seven hours later, well into the eventide gloom of Christmas Eve itself, cradled as he was in the arms of Sheriff Belouff and Deputy Patterson. So much for my little impromptu Christmas eve house-visit.

Instead there was Lionel blubbering like a kid on the first day of school, Burleigh County’s finest manhandling him up the garden path to the icicled veranda where he wilted in their arms and vomited on the front stoop. And all through that hapless night his wretches eddied across the yard to pierce the wafer strip walls of my bedroom. Outrageous to admit it now but I found myself tugging on my gabardine to pick my way over there in the snow some hours later. I didn’t cover much distance though. Lionel’s voice brought me up short a stone’s throw from his bedroom window. Belouff and Paterson had long since taken their statements and left. Lionel was alone, muttering and bereft. His words stung me, before I realized they couldn’t possibly be for me.

You’re low. And you’re cheap. Vindictive. Spineless. Or don’t you see it? It’s nothing for you to stoop so low as to wrench another from me? And one so painfully innocent of your omnipotence. How big of you. Wasn’t Hannah enough? Haven’t you gathered enough still-warm corpses to your polar embrace? You plug up your loneliness and your low, desiccated heart with the very thing you cannot have, the thing that makes us human. Then you leave us, drifting and destitute for meaning in this insensible life. Well you’ve lost me. My faith, belief, whatever prayers I’ve laid at your feet. I renounce them all. From this night onward I lend body, soul, spirit, whatever shreds of myself I can amass, to your Other. Because no matter how deep his darkness or how ruinous his sin, I can be assured he’ll take me in.

Then Lionel was sobbing again. I watched the broadside of his back heave awhile then left. It seemed his grief had left him crazed. It’d be half a year before I spoke with him again.

On a close, humid eve mid-way through June he dropped over for coffee unannounced. The funeral was long past but the gale was still blowing. You could see it in his eyes and the unforgiving slant of his mouth. His cup poised midway between tablecloth and parted lips Lionel upended and told me he’d spotted Francis on the bus the night of his death. Glimpsing a wash of canary yellow through the dead pines he’d even motioned to wave at his son. But something had stopped him. Becky Schumann on the seat next to his son, taking young Francis’s face in her hands and kissing him on the mouth. The gesture, sweet and lingering, rendered them heedless of the word around them. But Lionel only hoped it was transportive too, at least for a spell. Before the din of caterwauling metal pried them apart and eclipsed them from the world. Lionel had seen it all.

My family residence is a simple enough structure. A run of the mill pre-Revolutionary American farmhouse with two wide porches and four right angled wings, monochromatic and sprawling. Before it, twelve fertile acres run aground atop a tangled, formless-looking mound. The house sits rather securely on this. In truth, unless someone pointed it out you would never know the mound was there and fancy it part and parcel of the structure of the house itself. However, Harvey ‘Many Snapping Turtles’ Woholle, a local soil scientist and Chippewa medicine man told me the ‘Great Mound of Abundant Exchange’ as he put it, was of geographical and historical import.

According to Woholle the compacted dome of earth dated back to 1847 and was, he assured, nothing less than infused with spiritual flotsam. The mound and many others like it in the general area around Apple Creek once served as medicinal outposts for Lakota Sioux elders. It was what many believed to be a ritualistic sunkawakhan paha or ‘wishing mound’ if you will, where mostly children and the elderly would convene to donate the cartilage of dead horses in return for a single wish granted. There were plenty such mounds all over the county, Woholle enthused, nothing to get bent out of shape about. Didn’t I realize my next door neighbor’s property was virtually buried in one? Well what can I say. If Lionel cared, much less was aware of this, he never spoke of it to me.

And so the 2nd floor of my farmhouse, much loftier than Biddle’s, affords one a most delightful promontory. From up here I can see the studded perimeters of far-off Jezebel’s Plain and the golden, undulating swathe of Winona County further afield. But more crucially it lends me a clear, unimpeded view of Lionel’s own modest home and adjoining barn.

Presently he wasn’t there. Having ambled from the long-stemmed grass he now stood to the left of the dirt-track that runs the length of Apple Creek itself. It shackled the plasma in my bloodstream to find him there. And yet, if I’m entirely honest, I don’t know what else I expected to see.

Which brings me up to date. Only last week Lionel surprised me by paying me a second visit this year. We sat out in the tack room with the stove blazing. He asked me did I believe in ghosts, and if so, did I think we as human beings could reach out and touch the skin of one? And what would that feel like? The skin. Would the tips of our fingers come away with deep-freeze? Or something else entirely. The question, unbidden and entirely out of character, had taken me aback. All I could do was respond with the only truth I’d ever gleaned in all my years. I assured Lionel that if I could bring back my beloved I surely would, and, I dare say, by any means necessary. I regret our little chat now and yet…I’m strangely comforted by the notion it could have gone no other way.

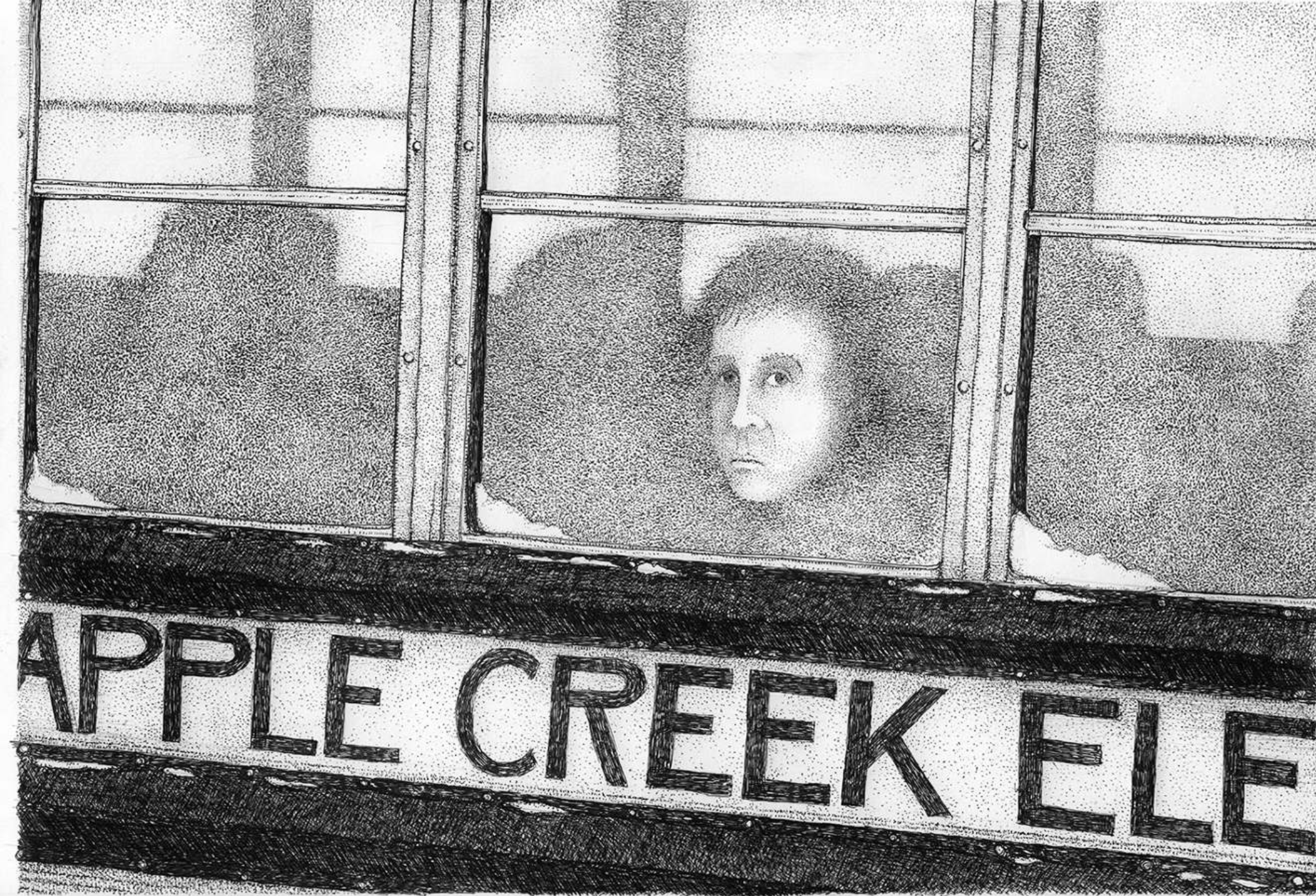

Lionel drew back from me and plugged a hand to his open mouth. With a nascent, glistening stare he duly confessed that for almost a week now he’d been watching his dead son riding the Apple Creek Elementary schoolbus from a secret vantage point deep in the glade. He stressed the angle of view, that Francis’s face wavered indistinctly at times, as though through light, wavering sheets of rainwater. But it was him rightly enough. His son’s profile was unmistakable. He swore he’d even waved to the boy as he had almost a year before, overcome with fright initially but also some dread gratitude he couldn’t articulate. The agony of it though, Lionel explained, was that each and every time the bus swam into view and his eyes fell upon the boy, he was alone, rapping ceaselessly upon the window of the schoolbus, seeking out a familiar face, surely the face of his father.

Lionel ended up in my arms that confessional eve, if you can believe it. I certainly didn’t. Even as he lay down on the comforter in the old tack room with me I did my best to comfort him. As a friend.

And so here it rolled, the Apple Creek Elementary school bus itself, unmistakably so, right on time, peeling down the pockmarked switchback, almost to the bend now. Didn’t it shudder in the North Dakota thrall? Didn’t it ripple like cold fire in the white distance? Didn’t it…defocus for a second or two? Or was that my own heartbeat, fluttering resolutely in my chest. All I knew was, right this moment, the margins of my gaze were not to be trusted.

I turned, plucked my spectacles off the nightstand. From this altitude I could see with relative ease the interior of the schoolbus. I noticed the cab was mobbed with children within, lolling side-to-side and bundled against the frost-webbed windows. They stood upright in pairs or packed assemblies of three or four. And sure enough, impossibly so, I heard them too, whooping and cheering on another joyous school year to a close. In all, there were more than 30 pupils and clearly, all available seats were occupied.

All except one. Just one space. A seat directly at the back and to the left of the cab, a space that if offered up could easily have accommodated two bodies, one large, one small perhaps. It was ideal for an adult and child. Yet nobody, not a single, opportunistic soul sat there. And to my creeping disquiet I watched Lionel Biddle board that same bus when it juddered to a halt just shy of Apple Creek, flash an expectant grin to the driver, then brush his way gingerly down the throng of pupils to sit down precisely in that space. He even bowed his head slightly to the left, looked downward and smiled. Smiled at nothing it appeared, at least nothing I could discern from here. But this I’ll never forget. Lionel Biddle smiled the way you yourself would smile at a loved one, perhaps a younger sibling or so, a daughter or a son, appraising the singularity of their features, the liquid glint of their stare, knowing full well they were the axis of your joy in a world all but riven with unkindness.

And Lionel, his brow beaded with sweat and haloed by a nimbus of dying evening light, dried his eyes before reaching out momentarily to touch the thin air alongside him. As I watched from Woholle’s Great Mound of Abundant Exchange I knotted my fingers for my sweet love. Then let him go.

At that same moment in downtown Bismarck, a couple of miles inland, Becky Schumann came to in Ward 423 of St Alexis Medical Hospital and beamed openly at her astonished parents. Overcome and disbelieving, they knelt to take her into their arms. As they did neither could have noticed the small object Becky looped into her cupped palms. She held fast to it, as if for dear life. She would stare at it long after her parents, immobile with awe, left the ward to arrange a homecoming for their daughter just in time for Christmas Eve. The object was simple enough, fashioned out of salt dough and rudimentary in execution, something poor misbegotten Francis Biddle had pressed to her on that perilous ride home exactly a year ago that day. A horse in mid-stampede, it’s long, flowing mane aflame it appeared, but strangely cold to the touch.

And yearning to see Francis Biddle more than anything in the world, Becky Schumann clasped the flea-bitten mare tightly to her chest and struggled to fight back tears.